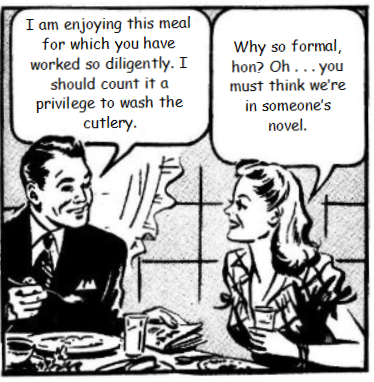

Writing Readable, Believable Dialogue

It doesn’t have to be that difficult.

Image credit unknown. Dialogue credit Easy Reader Editing.

I love listening to people speak. I love the differences in their voices . . . some are clear, some are husky or gravelly. Having a husband whose voice is very deep, I tend to notice when a man's voice is more in a tenor range, and it bothers me a bit, probably because I'm used to a lot more color and richness on an everyday basis. But accents . . . I enjoy listening to people who didn't grow up near where I did, because their accents are different than mine.

Everyone Has an Accent

Whether it's a "foreign" accent or not is all in the perspective of the person speaking and the person listening. Of course I can't hear my own in the same way a friend from England would, and vice versa. I grew up near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the US, and I don't know how I escaped it, but I do not speak Pittsburghese, and thank God for that. I love my Pittsburgh friends, but that accent gives the listener a distinct impression of their IQ level at times, and it's not a flattering one.

I imagine every part of the world has its own area that sounds "lesser" to others, whether those people deserve that label or not. Why else do scriptwriters call for a twangy Southern US accent when there's a dumb guy to cast, or a Cockney accent when auditioning for a working-class Londoner?

The Challenge When Conveying Local Speech “Flavor”

Writers face a special challenge when trying to convey speech accents in a novel. Not only do they have to incorporate regional speech patterns, but they have to do it:

authentically—if the local flavor doesn't sound right, anyone from that area who reads the book will be put off, perhaps even insulted

accurately—if the correct region isn't used, readers will know it and won't hesitate to pan it in a review

without overkill—a little bit goes a long way

Authenticity and accuracy sort of go hand in hand.

Whereas a British person who is writing about an American character may be under the impression that all Americans say "y'all" (and sometimes "all y'all") when referring to more than one person, those from Pittsburgh (my easiest frame of reference for this post) tend to say "yinz." And if you've written a character from New Jersey, they may say "youse" instead. Not everyone speaks like that, certainly, but you should at least get it right if you use it.

Accuracy means that you won't have your Australian character calling a woman "mate," since men only use "mate" for other men. Italians have a phrase, "to give bread for focaccia," which means you've responded to an offense with an even bigger offense . . . perhaps the American version that comes closest would be "to add insult to injury." And before the Harry Potter series and the advent of the more casual British literature, how many American readers knew that "trainers" were sneakers and a "jumper" was a sweater?

Overkill is a factor that should be given great consideration.

How much is too much slang or regional-ese? Dialogue can be enhanced and made more authentic by the use of these things, but there comes a point when it can become a distraction to the reader. I don't want to read about the guy from Western Pennsylvania asking, Yinz gone dahntahn to wutch the Stillers n'at? which translates to "Are you (all) going downtown to watch the Steelers?" The n'at ("and that") is one of those things people add and I don't know why. But it's tiresome to read line after line of dialogue that's essentially a foreign language while still being written in your own.

One of the ways to show some regional color without becoming laborious is to highlight a phrase or two without making it a constant thing. Considering that nobody speaks the way words are spelled, and if we wouldn't think of writing all our characters' dialogue phonetically, why do we assume we should do it for the characters who speak with an accent we don't consider "standard"?

There are ways to show it without forcing it.

A character can lapse into southern drawl when she's tired or angry, or a person can say a phrase like the above-mentioned downtown Steelers game (written typically) and another character (or the narrator) can note something like this:

Though she'd lived all over the world for more than two decades, there was something about being in her hometown for a few months that brought her own accent to the forefront and made her words come out sounding more like “dahntahn to wutch the Stillers,” and he smiled as he watched her in the midst of her family, each of them talking over the others in their excitement.

If you write characters with particular accents or regional "giveaways," it’s important to manage it without overdoing it.

Written Dialogue Should Sound as Natural as Spoken Conversation

I'm not sure how this happens, but for some writers, there is a major disconnect between conversing with people in real life and writing about people conversing. Why is writing dialogue so difficult for people who talk to others on a regular basis?

I think the major hurdle for many writers to overcome is making dialogue "proper" according to grammar rules. There's only one problem with that: real dialogue rarely sounds grammatically correct.

Before you write dialogue for your characters, watch people for a while, and listen to them talk. Yes, I'm asking you to stalk a little . . . for research purposes, of course. I'm willing to bet you’ll see at least a few of the following:

Contractions—Most English-speaking people use contractions, and yet so many writers are shy about using them for dialogue. "I do not understand" sounds a lot more stiff than "I don't understand." If your novel has a character who never uses contractions (much like Data in Star Trek: The Next Generation or Ziva from NCIS), it should be used as a distinguishing trait for a particular purpose.

Multiple Threads at Once—Any parent can relate to this. Or anyone who's looked at a chat window between my bestie and me. More often than not, there is more than one conversation going on at once, even if there are only two people involved. Somehow, we keep it all straight; conversation is rarely linear.

Mishearing—Conversations happen in a variety of places, and not all of them are quiet. Is your character talking on the phone, or are children playing around those talking? Someone is bound to say, "What?" at some point. My specialty, according to my husband, is talking to him from two rooms away in our house. I get a lot of responses that sound something like, "I can hear you but I can't understand you," and "You're not talking to me, are you?"

Getting Sidetracked/Self-Interruption—These two sort of go hand in hand. I get sidetracked all the time when I'm talking, and my kids make fun of me for it. I tend to be thinking of lots of things while talking, and this results in my sentence either changing midstream, or fading off altogether. Real conversation between me and my daughter in the car:

Me: I'm so thankful . . . [gets distracted by oncoming traffic]

Ellie: [waits a few moments, then speaks] . . . for . . .?

Me: [looks around] Four what? Where?

Ellie: Thankful. For. What. What are you thankful for? You never finished.

Me: Oh . . . I'm thankful someone's picking up your brother so I don't have to.

Body Language/Movement—These are essential in conversations. People don't stand straight at attention, facing each other to deliver their scripted lines in a tidy order. They move, they fidget, they pace, they do the dishes or fold laundry or any number of things. Your body language can help you or give away all your secrets.

Sentence Fragments—These differ from self-interruption or getting sidetracked, in that you don't need to be sidetracked to speak in fragments. People don't converse in the manner we all had to use in high school English tests, where we had to put our answer in the form of a full sentence. "What's for supper?" "Chicken piccata." You'll hear that as an answer far more often than "For supper, I'm making chicken piccata."

Age Is Relevant—Children don't sound like adults when they speak (though they do come up with gems every so often), so don't write the six-year-old's dialogue as if she has the insight and wisdom of a sixty-year-old. Kids are pretty simple: they want things and are happy when they get them.

These represent a fraction of the things to consider. There are awkward silences. Sometimes when people talk, they can't always recall the facts, so their speech is peppered with uncertainty and fishing around in their brains for the right word. Someone might always say, "Ya know?" between phrases. Be careful to not overuse such things, though—it can become tedious for your reader to sift through.

What You Shouldn’t Hear in Dialogue

Info Dumps

Recently, I wrote a post about the Dreaded Info Dump and how to spot and remove it from your narrative. Dialogue is often a breeding ground for info dumps.

I always think of the boss who talks to his employee while perusing through the employee's file folder.

"As you know, Joe, ten years ago when you were just a rookie, you took down that laundry-laundering operation singlehandedly even though your dog's cousin was going through psychotherapy for his issues with the neighbor's cat. I know that caused your divorce, but you can't keep blaming yourself by refusing to go to the laundromat."

Constant Use of Direct Address

When you talk with a friend, how often do you use that person’s name during the conversation? My guess is once. Maybe twice. But you’re not likely to start off each sentence with the person’s name, or to intersperse it every few lines. Your book’s dialogue shouldn’t feature it, either.

Overexplaining

This can come in the form of an unnecessary dialogue tag: if someone is sad and they’re crying, and they’ve said something that indicates how sad they are, it’s not the time to add “she wailed tearfully.” If your character is a burglar and he spots security cameras in the home he’s burgling, there’s no need for him to say, “There are cameras over there. They can see whatever we’re doing, and we won’t be able to get away with our crime.” If he simply points and says, “Crap. Cameras,” the readers will fill in the rest.

Awkward Bits of Information That Have No Other Home

Don't be afraid to read your dialogue aloud after you've written it . . . to "speak it out." It may sound natural—or you may come to the sudden realization that it doesn't. Picture yourself saying those words to a friend (or an enemy, depending on the dialogue).

Think of those awkward homemade commercials—Hey, Susan, you're looking so fit and trim! What's your secret? Is it that new 24-hour gym, Fat2Fit, at 123 Barbell Street?—and . . . don't do that.

People don't speak perfectly. Dialogue is not structured the same as a prepared speech given to a crowd, and is more often than not grammatically incorrect. Just let it happen and don't stress the specifics.