Plagiarism: Yes, It's Always Wrong

And don’t ask your editor to help you steal more effectively, either.

Background image: Soumil Kumarvia via Pexels

The average person would never dream of walking into a store, picking up a cart full of groceries or an armful of clothing, and walking out without paying for it. But that same person may not think twice about looking on a pirated book website, or downloading free music that’s not actually free (thank you, Napster generation).

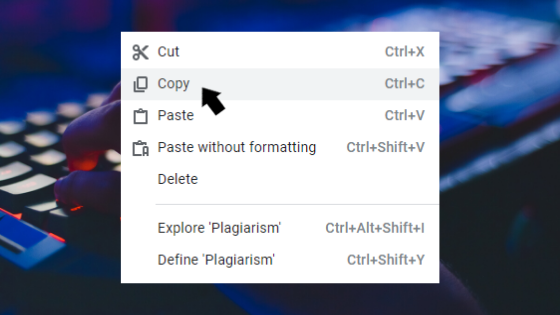

Even worse, that same person may think it’s okay to copy and paste portions—sometimes extremely large portions—of text from a published work and use it as their own.

If you are that person, I feel the need to tell you this: you will be caught. It may happen right away, or it may happen after enough time has passed that you think you’ve gotten away with it, but trust me on this one. It will catch up to you in one way or another.

Consider the following instances of plagiarism (all true):

An editor is working on a manuscript, and though the plot is vaguely familiar (formula writing often is), there’s something about the phrasing in a particular chapter that keeps niggling at the editor’s brain. A quick online search of a sentence or two reveals that the entire chapter was lifted from someone else’s novel—a novel that the writer enjoyed, but one that didn’t gain mega-popularity, thus fooling the writer into thinking no one would notice.

A professor is grading a student’s paper and notices that the writing style suddenly improves beyond the student’s previously shown capabilities. He runs the dissertation through a plagiarism detector and is not surprised to find portions directly copied from Wikipedia entries and other online sites.

A professor is not grading a student’s paper. Why? Because the paper in question was the professor’s own paper from when he was a student, copied and handed down over a couple years, name removed at some point, with a shiny new cover sheet added by said student.

An editor is bothered by an odd sentence that not only doesn’t sound like the author, but doesn’t even seem to fit the scene. The editor tries to recast the sentence and finally gives up, asking the author what it means in this context. The author says she “found it online and liked it,” so she used it. The editor, now more curious than ever, does a search and discovers the line is from an old poem (Yeats, no less), and that the author took the line from a website that showed examples of personification (with the website author also not citing the original sources).

Editor #1 sees that a newer colleague, Editor #2, has taken entire pages from Editor #1’s website and copied them to her own, changing only her name and email address. Editor #1 notices this immediately because Editor #2 is very proud of her new website and has told coworkers to “check it out.”

In each of the above situations, the plagiarism was caught.

In the first instance, the writer could have been sued, had the editor not caught the plagiarism before the book was published.

In the third instance, the student failed the course.

In the final case, Editor #1 had to confront the colleague and ask that those pages be taken down, explaining that not only was this outright theft, but that Editor #1 had paid for a professional copywriter to put together those personalized pages with SEO (search engine optimization) specific to her business and goals.

Writers who plagiarize may not be thrilled when they get caught, but it’s much better to have an editor or colleague tell them what they’ve found before a lawyer contacts them with a list of demands and a hefty bill to go with it.

In the creative world, there are times when it’s hard to come up with original ideas, but it’s possible.

As author Jack Tyler wrote on his blog, Jack’s Hideout, recently,

“We’re all inspired by everything that has come before, and some of us can take those things and mold them into new works that carry that engaging touch of familiarity while still being “original.”

Music is made up of the same twelve notes, and yet it sounds different in every culture because of the way those notes are arranged. Stories are composed of the same words we speak every day, but those words are put together in a pattern that’s unique to each writer. Or they should be, anyway.

Just because something is on the internet doesn’t mean it’s free to use.

This is something I never gave a thought to when I was a new blogger, years and years ago. I would never steal someone’s words, but for some odd reason, it never connected with me that I needed permission to use the images I did for my blog posts. To be fair, I was new to the game and assumed that any image I found under my keywords was available for use unless it had a watermark on it. I would check for a watermark or a copyright, and if I found none, would download the picture.

However, once I learned how wrong that was, I quickly changed my approach. Now, I’m careful to credit any images I use, and I’ll use my own if possible. Even so, once in a while, I mess up out of ignorance. A few months ago, I submitted an article using an image that I thought was public domain, only to have the publication reject the story until I replaced the image.

Defining plagiarism is easy.

According to the Merriam-Webster online dictionary, to plagiarize is “to steal and pass off (the ideas or words of another) as one’s own : use (another’s production) without crediting the source,” and also “to commit literary theft : present as new and original an idea or product derived from an existing source.”

In the article “What is Plagiarism?” on plagiarism.org, it’s stated bluntly: “In other words, plagiarism is an act of fraud. It involves both stealing someone else’s work and lying about it afterward.” (Emphasis mine.)

To put it simply: if you use it, get permission.

Give credit. Add source and quotation marks. Acknowledge in some way that this work is not your own. Don’t sneak it in and hope that no one notices, or worse yet, ask your editor to “change the wording around a little bit so it sounds more like me.” (Yes, this has happened to editors I’m acquainted with, and yes, they all gave an emphatic NOPE to the requests.)

If it’s important enough for you to write about, it’s important enough for you to do your own research and come up with your own ideas. Period.

UPDATE 10.12.20: Lisa Paul from Educationdegree.com contacted me to share a terrific resource. Enjoy! Preventing and Recognizing Plagiarism and Cheating: A Guide for College Teachers and Students

If you enjoyed this post, share it with your writing friends! The Pinterest-friendly image is below, and all the social media sharing buttons are right below it.

Share the love!

Visit my Pinterest boards to find helpful writing tips.